God's Dazzling Darkness

Our Sunday morning adult Bible study was coming to the end of the book of Ruth, when we read the people's blessing, those who had witnessed Boaz' redemption of Ruth by the city gate: "May your house be like the house of Perez, whom Tamar bore to Judah" (4:12). I asked if anyone knew who Perez and Tamar were. One hand went up. So off we went to Genesis 38, and the story of poor Tamar, whose marital fortunes were, let us say, tragic. Her first husband Er was wicked, so the Lord "killed him," then Er's brother Onan was supposed to step in to provide Er an heir, but he pulled out at the last minute (literally), so the Lord "killed him also." I discerned uncomfortable shifting in some Sunday school seats. As a young man, Albert Einstein lost his faith in traditional Judaism upon reading a similar passage in Exodus 4:24, "And it came to pass on the way, at the encampment, that the Lord met him [Moses] and sought to kill him." What do we make of such passages? They are certainly unsettling, and provide an existential urgency to the proverb, "The fear of the Lord is the beginning of wisdom" (Pr 9:10). My usual response to the anxious queries of parishioners is that these are Hebrew idioms which attribute the death or illness of a person to God's judgment for wickedness. I try to move them away from the image of God as Zeus, capriciously throwing thunderbolts from Mt. Olympus. I remind them of Romans 8:1, "There is therefore now no condemnation for those who are in Christ Jesus." But there is no denying a terrifying element to God's power. "Your wrath has swept over me; your terrors have destroyed me" (Psalm 88:16). "Knowing, therefore, the terror of the Lord, we persuade men" (2 Corinthians 5:11).

Our Sunday morning adult Bible study was coming to the end of the book of Ruth, when we read the people's blessing, those who had witnessed Boaz' redemption of Ruth by the city gate: "May your house be like the house of Perez, whom Tamar bore to Judah" (4:12). I asked if anyone knew who Perez and Tamar were. One hand went up. So off we went to Genesis 38, and the story of poor Tamar, whose marital fortunes were, let us say, tragic. Her first husband Er was wicked, so the Lord "killed him," then Er's brother Onan was supposed to step in to provide Er an heir, but he pulled out at the last minute (literally), so the Lord "killed him also." I discerned uncomfortable shifting in some Sunday school seats. As a young man, Albert Einstein lost his faith in traditional Judaism upon reading a similar passage in Exodus 4:24, "And it came to pass on the way, at the encampment, that the Lord met him [Moses] and sought to kill him." What do we make of such passages? They are certainly unsettling, and provide an existential urgency to the proverb, "The fear of the Lord is the beginning of wisdom" (Pr 9:10). My usual response to the anxious queries of parishioners is that these are Hebrew idioms which attribute the death or illness of a person to God's judgment for wickedness. I try to move them away from the image of God as Zeus, capriciously throwing thunderbolts from Mt. Olympus. I remind them of Romans 8:1, "There is therefore now no condemnation for those who are in Christ Jesus." But there is no denying a terrifying element to God's power. "Your wrath has swept over me; your terrors have destroyed me" (Psalm 88:16). "Knowing, therefore, the terror of the Lord, we persuade men" (2 Corinthians 5:11).Frank Kermode, in the most recent New York Review of Books, notes that Bloom, a Jew, is voicing a lament on behalf of the entire Jewish people for God's destruction of his covenant people. In Bloom's reading of the Tanakh (the Hebrew Bible), Yahweh is troublesome, moody, alarming, and unreliable; someone who bears no resemblence to the Christian Father. This early tribal image of God is superceded first by later redactors (Priestly and Deuteronomic writers), and then by the Christian and Moslem appropriation of the "Old Testament." Bloom is waiting for God to do something again, but hopes it is not a command to rebuild the temple, which would ignite a Palestinian conflagration. The value of Bloom's reading is not that it reflects good biblical scholarship (Bloom is a literary critic), but that he is unafraid to confront the verses which disturb our modern sensibilities. He "un-domesticates" Yahweh, and makes him a lurking, moral presence in our immoral world.

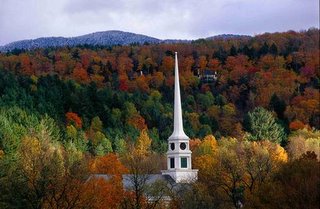

Soon hordes of children and their parents will flood movie theaters to see an adaptation of the first of C.S. Lewis' Narnia Chronicles. I remember one particular line from the book which resonates with this discussion of God's darker nature. The children are warned that Aslan the lion (an allegorical Christ) is no tame lion, so they should be careful. The Triune God we are currently dealing with is also no tame lion, and it would serve us well to be mindful of God's unpredictable sovereignty. Ananias and Saphira come to mind here (Acts 5). The great 17th century metaphysical poet Henry Vaughn captures this in his poem "The Night (John 2:3)."

There is in God (some say)

A deep, but dazzling darkness; As men here

Say it is late and dusky, because they

See not all clear;

O for that night! where I in him

Might live invisible and dim.

Something to ponder as we make our way through the thickets of Advent.